Kristin Lyhmann

1. The kindred spirits Jan

Amos Komenský and Ingeborg Refling

It was in Sárospatak that Commenius (Komenský) tried

out his Scola Ludus with didactic

theatre played by children. His work was carried out in exile and in opposition

to his contemporary educationalists.

I have been given the opportunity to recount another

pedagogical theatre: To the Norwegian writer and educationalist Ingeborg

Refling Hagen (1895 – 1989), the aim was to make classic literature available

to children in postwar

In the days of Commenius, the absolutism gained foothold

in

Commenius and his 300 years younger kindred spirit

Ingeborg Refling Hagen (hereinafter referred to as IRH) had almost identical

thoughts on why and how children could be educated through theatre:

Man’s harmonious development, the refinement

of the spirit, ”cultura ingeniorum”, must emerge spontaneously from the child

itself, driven as it is by its natural urge to question, to imitate, to play

and to learn, by the natural joy it experiences in mastering the situation and

in feeling free. (…) The parents of small children “must always ensure that the

child is never wanting in joy”, says Commenius. (Blekastad 1973)

The joy and the festival constitute the core elements

of both IRH’s and Commenius’ education.

I shall offer an example of one of IRH’s theatre

pedagogical methods: To grasp any opportunity to create a festival and any

festival to create theatre. This should be interpreted as a theatrical

adaptation of literature, in which all those who are present become active

participants. IRH’s concept of theatre was closer to the medieval participating theatre than the sharper

differentiation between the performer and the recipient of the renaissance and

posterity.

First, I will share an impression of the annual flower

festival in honour of our national romantic writer Henrik Wergeland (1808 –

45). The Polish have their Mickiewicz; the Czech their Komenský; the Tuscans

their Dante; the Swedish their Almquist. In

I perceive IRH as a medieval ”play leader”. The flower

festival she has created cannot be understood as a pedagogical expression

unless the observer is familiar with the conditions under which her life

unfolded. Therefore, the second part of this article is devoted to her

profoundly personal relationship to the classic European literature.

In part three, I will

discuss connections between the flower procession and a mystery play of the

High Middle Ages – and attempt to make a step further: Could it be that we also

see an outline of school drama in the Wergeland Festival at Tangen?

Personally, I am a child of IRH’s theatre pedagogics,

and can only offer my own impressions ”from within”. As a theatre researcher, I

have taken interest in the medieval theatre. It is from these two angles that I

will approach my theme.

Wergeland’s memorial day 17 June, is one of IRH’s

excuses to make a festival. Each year on this early summer’s day, a procession

advances through the lush landscape. The road is framed by blooming cow

parsley. Old and young carry branches weighed down by elaborate paper flowers –

a specialised craft developed for this particular day. The procession is

organised in “wagon scenes” and walking group scenes. In the course of the

procession the spectators can be absorbed and become participants. There is no

uniformed police here, but an omnipresent play leader. She has her own cart in

the procession, but can just as well be spotted walking next to the groups:

Listening, singing, encouraging – and offering a flower branch to a spectator

along the route.

Beneath a swaying ceiling of flowers, Wergeland’s

words emerges from each wagon, each group – carried by strong or frail voices,

in the shape of singing or speech; all mixed with a solid portion of children’s

laughter.

(Florilla, a character from Wergeland's theatrical writing, leads the way in the flower procession)

In front, FLORILLA can be found carrying a large

basket. Her basket includes one flower of consolation for each human folly:

With a star gleaming white narcissus

she chases off dark thoughts; with the bird's-foot

trefoil she softens the tongues of gossip…

The 21 BLOOMING THORN BRANCHES walk at the very back

of the procession – singers named after two political poetry cycles, written

1842 to convince the Norwegian Parliament that the Jews must be allowed to enter

the country. The singers carry blood red flower branches, one for each of the

poems. The song from beneath the bobbing rose branches goes thus:

What if

its

green valleys to them [the Jews] in hospitality.

What

if its cool blood

could

once in a while be mixed with the oriental...

(It goes with the story that the Jews were let into

The procession worms

its way through the landscape between FLORILLA and the THORN BRANCHES. Wagons

with children too small to walk themselves are pulled by tractors driven by

young girls in long gowns and with tiara-crowned heads.

Then, male voices are detected, and the story of the

farmer Niels Justesen unfolds:

Härjedalen and Jämtland, the treasured landscapes once lost by

Women from Linderud, an

The whole procession comes to a halt. A fir tree and a

maple tree have entered an argument of whether hospitality pays off. The

dialogue is passed from tree to tree along the route.

THE EAGLE BOYS can be found in various places in the

procession. Their poem is Følg kallet

(Follow your vocation) – a poem about the writer born into a small language

group: He is like a golden eagle bound by a chain around his leg.

In the middle of the procession, transported by her

own cariole like a princess, STELLA advances. Stella is the name of the beloved

in Heaven in Wergelands poetry. In the prosession she is the centre of

attraction.

Thus, Wergeland’s ”golden rings” are strewn along the

route. Once it has returned, the recitation takes place in a more ordinary

theatrical fashion: From the outdoor stage and in the garden, and at Tangen

Community House in the evening.

But that is another story.

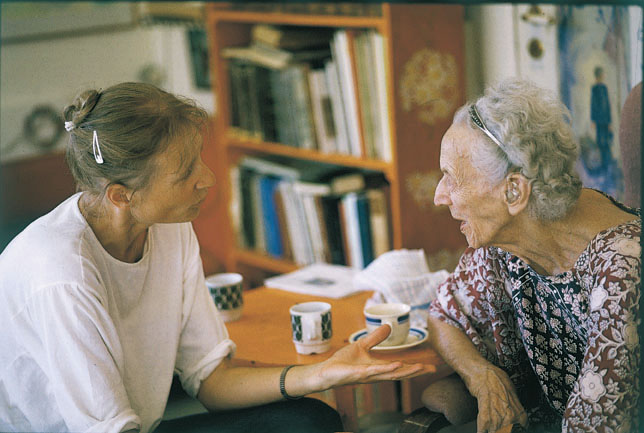

(Ingeborg Refling

2.2 The writer Ingeborg

Refling

At this time, she had established herself in Oslo.

As a young writer,

she wondered why Nationaltheatret did not assume the management of our greatest

playwrights. Ibsen was played abroad; consequently, he was also played at home.

But Wergeland’s theatrical production was of a larger scale, stretching from

folktale plays to political one-act plays, from historically rooted themes to

contemporary political farce; he anticipated the absurdism and Norwegianised

the language. Practically all of it was written before we had a permanent

theatre to bring the material to life on stage.

When Nationaltheatret refused to play Wergeland, IRH

decided to do it. Supported by young artists, especially painters, she managed

to stage Det befridde Europa (The

liberated

IRH could now focus on her next cause: The fight

against Nazism. She had completed two extensive study trips to

The imminent issue

was to raise funds for the

Simultaneously, she started working with children.

“The desire for freedom and value awareness must flourish in man’s mind if we

are to survive as a nation. We must let the poetry teach us these things”, she

said in 1938, and invited thousands of children from schools in the entire

Eastern Norway to celebrate Wergeland’s birthday the same year in Eidsvoll, a

few miles south of Tangen.

In Norwegian history Eidsvoll is a symbolic place: On

Our first 17 May procession was a political

demonstration procession.

Many years passed after this incident without any

celebration of the constitution.

IRH’s establishing of a 17 June-festival at Eidsvoll,

rooted the flower festival in our history of freedom. The program was carried

out under a freshly painted banner on which a Wergeland quote could be read: “A

free country has honour enough”.

The war came to

The blacker the looming political clouds turned, all

the more beautiful and eventful she would make the children’s festival. It was

urgent to make visible that we had something to defend.

However, a death sentence was towering above her for

her illegal daily, and she was arrested in 1941. She infested herself with

diphtheria and was transferred from the prisoner’s camp at Grini to Ullevål

hospital, where the doctors made sure she stayed mortally ill for three years –

while she was teaching literature to the nurses!

For who came to her rescue during her torture: Don

Quixote.

Who gave her the insight into the psychology of

torturers, thus providing her with the tools to endure: Shakespeare’s two

Richards, the II and the III.

Who showed her a way out of hell after having

completed a journey to the depths of Lucifer’s kingdom of ice: Dante.

Who could stay on the bonfire without losing sight of the target: Jan Huss.

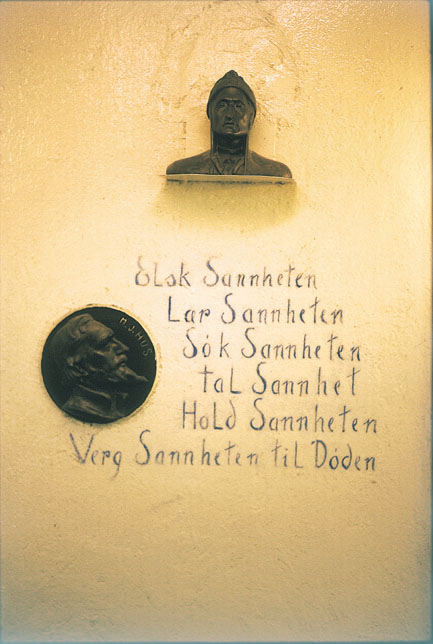

(In the firewall by her working space in the living room, IRH has framed two reliefs – one of Dante and one of Huss. Between the reliefs, she has quoted the parting letter written by Huss before he died on the bonfire: ”Love the Truth, learn the Truth, seek the Truth, speak the Truth, hold the Truth, defend the Truth until Death”.)

The authors and their figures were her helpers. She knew them by heart.

The nurses smuggled her literary studies out of the

hospital. These handwritten letters from her imprisonment became the foundation

for her literature teaching after the war.

Moreover, she went on

hunger strike and played mentally deficient during interrogations. She did not

give in. Eventually she was declared insane, her case was abandoned, and she

was sent home to Tangen in 1944. As long as the war prevailed, she had to

continue to play insane, while she in secrecy relearned how to walk.

She would stay here

in her childhood home “Fredheim” for the rest of her life. This is where she

started her extensive literary activities among children and adolescents.

In 1946, Eleanor Roosevelt invited IRH among 260 other

women from all over the world to the conference “The world we live in – the

world we want”. IRH was referred to in the American press as “

During her imprisonment, she had promised herself that

if she ever came out alive, she would teach every child she met in the

literature that had carried her though the torture. In 1981, the last volume of

her autobiography was published. She was then 86 years old. The book was called

Løftet må holdes (The promise must be kept).

She stated here that keeping this promise had become the heaviest mission she

had ever taken on herself.

The country was now to be built, providing everybody

with houses and most people with cars, and we entered into the NATO. From IRH’s

point of view, this meant opening the door to cultural imperialism. English

became the language of the teenagers for expressing emotions. During the years

prior to

As a preserver of culture, she coincided with her

times.

However, she did not take the side of her times’

educationalists regarding the matter of giving the smallest children access to

the greatest literature.

The protective pedagogy had as a result that a number

of unpleasant words disappeared from the children’s schoolbooks, such as

“death”, “suffering”, “consciousness” – even the word “love”. In the same

manner the Bible stories in the schoolbooks were replaced by moralising

parables about good and bad children.

She referred to the 1950’s and 60’s as the hardest

years of her life. Before the war, the image of the enemy had been clear: The

Nazis with weapons in their hands. But fighting the Americanisation was seen as

a battle against windmills. As an institution, the school failed to recognise the

danger of turning dull during times of prosperity.

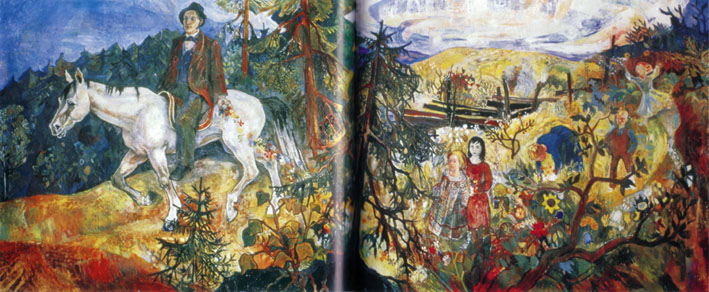

IRH formed alliances with individual teachers. She had two schools decorated by leading Norwegian pictorial artists. Desks, wood-box, staircases, ceilings, lecterns – the rooms were decorated everywhere. The Stein school close to Eidsvoll was finished already before the war, parallel with the first 17 June gatherings. Reidar Aulie’s painting bearing the name of one of her children’s song, I natt red’n Henrik forbi (Last night, Henrik rode by), fills the entire back wall of the classroom for the pupils 9 – 12 years of age.

(Reidar Aulie’s painting ”Last night, Henrik rode by” at the Stein school.)

This picture belonged to a small group of country

children from it was painted in 1939 until the school was turned into a museum

in 1972. This could invoke associations with Giotto: He painted a fresco in the

cell of each brother of the order. One painting per monk...

Immediately after the war, IRH made artists decorate

Strandlykkja school between Tangen and Eidsvoll, in accordance with the same

principles. “Those who build palaces for children, deconstruct the prisons”,

she said.

The promise was to be kept. It was to be done by

bringing beauty to the school building, by directly reading with children and

through her own literature. She planned The

Life Frieze in 12 volumes. It was intended to be a combination of fiction

and literature communication – a didactic work related to Dante and Almquist. Her plan did not coincide well with the modernism. After four

volumes, the publisher stopped the project. She could see only one passable way:

Opening her home for children and adolescents. Giving way for the teachers and

artists – and carrying out her literature communication efforts independently

from publishers, schools and theatres.

2.3 The writer Ingeborg

Refling

I happened to be one of these children. To me, she

flung the doors wide open to the world literature. And like all the rest, I

received special treatment: My mother was Danish, and I was brought up on H. C.

Andersen. But IRH soon revealed that I did not know “my own Danish culture”. I

had not read Pontoppidan, Kidde, Blicher, Kierkegaard… so she sat down in the

fireplace corner with me and read to me – novel after novel. And when I

prepared to take the introductory exam in philosophy at the University in

A young painter stopped by before he was going to

That’s how she was.

A child could be sitting on her lap twisting her

silver filigree brooch around its hand while she was reading out loud. If the

child interrupted with a question, she would answer it. I had to realise that

she deemed the five-year old’s need for an answer for more important than my

own exam preparations. But “What Little Ole misses, Ole will never catch up

with”, as was written on a door in the Stein school. It often occurred that the

kids who played in the living room in “Fredheim” learned our lines as quickly

as any of us who were practicing for events like the Wergeland Festival.

In an article, she accounted for her pedagogical

attitude thus:

I believe no more in intelligence tests

than I do in astrology. I have no business with the pedagogy that locks some

doors and leaves others open. I leave all doors open, and follow the child to

where it decides to go by its own initiative. (...) A three-year old is one of

the many we have to lift up to the microphone on the 17 June gatherings, for

they would be deeply offended had not also they been allowed to read The Swallow. They know it, don’t they?

We have to accept it.

I will not hide the fact that certain

educationalists are shocked upon hearing the kids racing ahead like this, page

up and page down – one after the other. According to theory, this is not

correct! “Is this not detrimental? It is not possible that the children can

understand it all!”

It has been proven to me upon many

occasions that children understand a great deal more than what the incredulous

adults believe. But I willingly answer that as long as the unintelligible

material is meaningful, it cannot be detrimental. For it will live and develop

wherever it is allowed to enter. My theory is built on the ability of the true

human expression to explain itself.

This answer should suffice; at least until

a T.S. Elliot of pedagogy comes along one day and puts a name to the method.

Besides, I doubt that the educationalists would be all that shocked if they had

read their Commenius more diligently.

Instead of asking

what I have done to my students, you might as well ask what Wergeland, Kinck

and Homer have done to them. These were my students’ discussion partners. One

does not leave such company unaffected. I sit next to them and share the

child’s experience, but what I initiate, is the conversation with H.C.

Andersen. I do not lecture. I do not intervene until the child turns to me and

asks what the writer meant with that. Or: “What is a knight?” Only then do I

consider myself entitled to an opinion as a member of the symposium.

As one will notice, I

deliberately take advantage of the fact that an environment has been created in

which poetry reading is a pleasure and taken for granted. The method consists

of the mutual encouragement between children and adolescents that connects the

poetry with the festival and flower procession on the Wergeland Day,

inter-human contact and life orientation. In addition, the seriousness and

missionary ardour in the young human is of great help. (IRH 1970)

Pestalozzi and Commenius were read loud when students

of pedagogics would visit. Her joy was beyond words when Milada Blekastad

translated The labyrinth of the world and

the paradise of the heart into Norwegian in 1955. In this world poem, she

could see a kinship with Wergeland’s Mennesket

(Man). In 1965, Blekastad’s translation of The informatory of mother’s school was published – and was

immediately included in the reading with the students in Fredheim. In 1958

Blekastad wrote the history of the ancient Czech literature in Norwegian. In

this work, the writer-educationalist Commenius is given the position in which

IRH sees her own work: The writer with a practical responsibility! The author

must be in close contact with his reader, and in times of hardship, perhaps

children are the only readers one can hope to reach. Finally Blekastad’s

doctorate thesis about Commenius was

available in a Norwegian translation in 1977.

2.4 The family as an

organisational model

IRH’s postwar cultural efforts were never organised or

registered. They were communicated via the jungle drums: One visitor would drag

another along to a weekly reading aloud session.

It occurred that we suggested organising ourselves –

if nothing else, then at least to be able to apply for financial support. The

answer was no. She probably felt that the Government should see for itself what

she was achieving and pay her accordingly. “The children of the people are the

Government’s treasure”, she said in a poem about the welfare state. But as it

would turn out, the Government was visually impaired. The solution was

remarkable moderation in the everyday life – and opening of all floodgates for

large arrangements such as the 17 June festival.

The closest I can get to a description of the

organisation, must be an extended family model. She was the “big mother” of a

wide-embracing, yet loosely composed commune.

The work was called ”Suttung” after a giant in Nordic

mythology. He guarded the bard’s mead. It has been told that whoever drank this

mead would become a bard or a wise man. Although the doors were open both

inwards and outwards of this reading environment, there were those of us who

grew up without leaving. For us, larger functions crystallised besides the

reading: In 1962, the first book was published by SUTTUNG FORLAG. In 1965,

SUTTUNGTEATRET moved out of private living rooms and onto the stage in Tangen

Community House.

“Fredheim” remained the centre, the pulsating heart in

the work. I have mentioned the reading aloud in the living room often enough.

But I have yet to describe what a factory

this living room was, and the Demostenes

training the readers were subject to: The Suttung Publisher’s books were

hand made during the reading aloud. True enough, they were stencilled outside

the house; but the actual binding took place around the large living room

table. And for months each year, the 17 June flowers were produced as pure

artistic craft in crêpe paper. Not two flowers were alike. Every single one was

fastidiously put together like coloured jewellery. The reader was forced to

make sure he was heard through perpetual sounds of paper crunching. That was

the vocal training we received. It would turn out to be sufficient for

succeeding on a large stage.

3. The flower procession, a

“modern medieval” theatre

It is fairly easy to discern formal connections

between the 17 June procession and the theatre processions of the High Middle

Ages: For example, the simultaneous scene principle, the blurred differentiation

between the performers and the spectators, the conducting play leader. The

similarity can also be found in the setting of a permanent theatre day in the

early summer. At Tangen, the

In the Mediterranean countries, the medieval theatre

is today replaced by the big religious festivals and their appurtenant

processions. The splendour in for example Sevilla’s Easter processions

constitutes a horn of plenty that knocks a puritan Norwegian completely off

balance. But IRH has experienced such saint festivals, and if there was one

thing she despised regarding children’s festivals, it was narrowmindness. It

may be from here that she has adopted the idea of not merely beauty, but extreme beauty in her expression. In Elx

on the east coast of

|

|

|

|

IRH had experienced saint festivals on Sicily and was familiar with the splendour accompanying these medieval processions. Here is an example of artistic craft in a Spanish Easter procession: Filigree braiding of palm leaves in Elx. |

A 17 June flower in crêpe paper, unlike all other 17 June flowers! This artistic craft was made in the living room in Fredheim during readings of Commenius, Dostojevskij, Victor Hugo... or perhaps a young Norwegian writer. |

In our nearer past, we have national procession ideals; first and foremost in the celebration of 17 May, the Norwegian constitutional day. About 1870 the 17 May procession started up as we have known ever since: A children’s procession with flags and singing and school bands all over the country. The only military element is the morning salute from abandoned forts.

(The annual 17 May procession on

Wergeland’s name is always mentioned in 17 May

speeches: Our writer and freedom warrior who left for

With our 17 May celebration, it may seem completely unnecessary with a Wergeland Festival a month later. IRH was not of that opinion. In the celebration on 17 May the element of theatre is missing.

What IRH accomplished, was to combine the spring

festival found in all religions with the abundant beauty in the saint festivals

of the south and with our own interpretation of a radiant children’s

procession.

In a country where the theatre of the renaissance as

well as the school theatre were imported in the coastal towns by a growing

lumber and shipping citizenship in the 16th – 18th

centuries, IRH discovered an older and yet more simple theatrical form that she

rooted in the inland during the 20th century. She combined the

modern school drama principles for participation with the didactic literary

tradition and a southern European festival beyond all limits.

Comenius had pointed out the way.

And in case of rain... well, then the Hedmark sense of

humour will conquer most obstacles. The beautiful flower craft is demolished in

five minutes. The paper colours pour down faces and festive costumes like

floods of lava. You can be sure that one of the participants of the festival

will immediately pull a Wergeland poem out of his sleeve:

Oh, sweet, gentle rain; og on!

Let your silver plectrum ring,

you will not startle the flower’s peace.

(Olav Bjørgum’s painting: Fredheim 17 June.)

4. Epilogue

IRH retired from the public, including the 17 June

festival, in the middle of the 1980’s. She retired while she was still able to

communicate clearly that she had contributed with her share.

She was more than 90 years old. But she continued to

make flowers and publish books until the day she drew the line herself. Her

sight had become too poor. Her hearing had been ruined already during the abuse

of the war. Her aesthetic sense had been so superiour that she refused to risk

having to deliver as much as one paper flower of inadequate quality.

Like FLORILLA, she had strewn her written and hand made flowers as a love hymn to the individuals in our nation. In the way FLORILLA concludes with her poem after a relatively crude farce of lies and deceit, IRH could also finish her operations as a play leader with the statement: “Thus a writer takes revenge!

---

An era had come to an end. Her closest family, meaning her family in blood, took up the gauntlet. Freshly made flowers sway through the early summer landscape. New children play Wergeland’s farces and sing his songs. The way folkculture have survived through family tradition in centuries, 17 June may also live side by side with what we refer to as “Time”, annually awakening the memory that “great literature actuate itself , as long as one makes way for it” – to finish off with one of Ingeborg Refling Hagens “golden rings”.

(Translation to English: Hilde Schmiedeknecht)

©Kristin Lyhmann 2002